11

May

2012

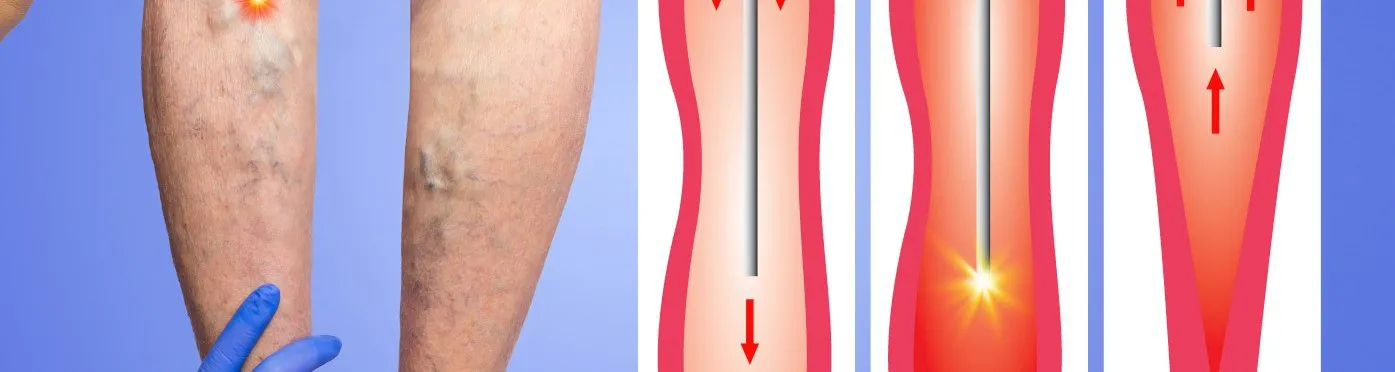

In approximately 2007 the NHS began to restrict access to vein surgery, such as endovenous laser ablation (EVLA) and sclerotherapy in parts of the UK. Recently this restriction has become much tighter and much more widespread.

The way the NHS funding is allocated across the UK differs from place to place. Each area is governed by a Primary Care Trust (called a PCT). The PCT gets a pot of money each year from the Department of Health based on the number of people in its area and what their health needs are thought to be.

The PCT then has to decide how it wants to spend the money on behalf of the patients in their area. The PCT will ‘purchase’ (also called ‘commissioning’) care from the hospitals who are providing operations for the patients – so for example the PCT will undertake to pay a hospital for doing 2,000 hip replacements per year and so on for each procedure. The cost of each operation is called a ‘tariff’ and this is fixed centrally by the Department of Health.

As a result of budgetary pressures most PCT’s are now prioritising various treatments. In other words, they make a judgement about what treatments are essential, which are important and which are low priority. They then decide which treatments they are prepared to commission from the Hospitals and which they are not prepared to fund.

As far as vein surgery is concerned most PCT’s now classify vein surgery as low priority and will not pay for it to be carried out except under certain specific circumstances.

So for example in most cases, in order to ‘qualify’ for vein surgery or treatment on the NHS a patient has to have veins so bad that they have caused a venous ulcer or are about to cause a venous ulcer if they are not treated. This accounts for about 25% of the total number of people with varicose veins, so 75% of patients with varicose veins will not ‘qualify’ for NHS surgery under the usual priority criteria.

Most PCT’s will not pay for patients to have treatment if their veins are painful, aching or throbbing, even if the discomfort is very significant. Naturally, veins that are just of cosmetic concern are not regarded as a priority by the PCTs.

Many patients complain about this, not just because their veins hurt, but because they are worried about developing skin damage to the legs if the veins are not treated. The argument most commonly used by the PCTs is that not all patients with varicose veins will go on to develop a skin ulcer – in fact, only about 30% of patients with varicose veins do go on to get skin ulcers.

If a patient did go on to get a skin ulcer then they would ‘qualify’ for treatment on the NHS.

These restrictions are now in force across most areas in the UK. The General Practitioners are often told not to refer a patient to the NHS hospital with varicose veins and if referrals are made they are sometimes intercepted by managers and returned to GPs.

Vein surgeons have been told not to put patients on the NSH lists if they do not fit the strict criteria and the hospitals are informed that if they do operate on patients who do not fit the criteria the PCT will not pay the bill.

This does leave the patient with painful varicose veins with little option other than to use compression stockings permanently or to seek private treatment for their varicose veins.

Private insurance companies (BUPA, AXA etc) will pay for their patients to have vein surgery for pain and discomfort even if the patient does not have skin damage.

For patients who are not covered by private healthcare, there are usually self-funding options available, which cost about £3,000 per leg.

Many thanks to the author of this blog Eddie Chaloner who is is a Consultant Vascular Surgeon practising in the UK.

Chaloner pioneered endovenous laser surgery treatment for varicose veins in the UK, which has revolutionised the treatment of this common condition worldwide. In 2003 he was the first surgeon in London and the South of England to use laser surgery to treat veins.

He frequently lectures and teaches on the subject of minimally invasive vein surgery and is a faculty member on a variety of training programmes including for theRoyal College of Surgeons of England, the Charing Cross International Vascular Symposium and the Venous Forum of the Royal Society of Medicine. He is also a member of the Vascular Society and of the Royal Society of Medicine.