The American Who Helped Develop Aesthetic Lasers

Dr Patrick Treacy shares a chapter from his new book entitled ‘The Living History of Medicine’

Dr Patrick Treacy has a new book out, and this time, he takes the reader on a journey with Osler’s famed ‘Goddess of Medicine’ in The Living History of Medicine. Here he shares one of the chapters entitled “The American who helped develop aesthetic lasers”, which explores the life of the American Scientist Charles Townes (1915-2015).

Charles Townes was born in Greenville, S.C., in 1915. He studied at Duke University before completing his PhD at Caltech in 1939. A stint at Bell Labs was followed by a faculty position at Columbia University, where he taught before moving to MIT in 1961 and finally to Berkeley six years later.

It is ironic now to think that in 1958 when he showed that a MASER could theoretically be made to operate in the visible region of the spectrum, his colleagues told him “that his work would have little relevance to the real world”. In 1958, the ‘hula hoop’ was the entire craze in Europe. Russian author Boris Pasternak declined the Nobel Prize in Literature because he feared the authorities would expel him from his motherland. I am sure the world changed considerably when Charles Townes received the Nobel Prize in Physics four years later.

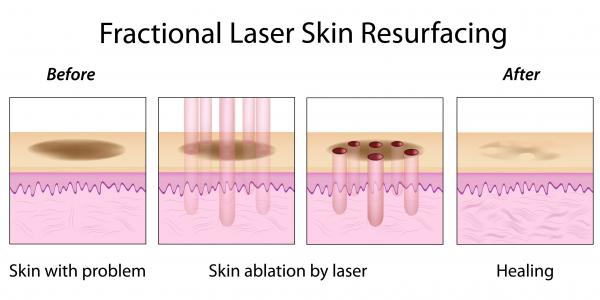

Today, lasers are used in every aspect of life, including an ever-increasing number of cosmetic treatments, including skin resurfacing for wrinkle reduction and acne scars, removal of tattoos, removal of hair, removal of pigmented blemishes (age spots and moles) and the treatment of vascular lesions (port wine stains and spider veins). In fact, the real story of lasers started many years before.

In the year of 1917, the great physicist Albert Einstein postulated that atoms could be persuaded to emit tiny packets of energy called ‘photons’ in his treatise “On the Quantum Theory of Radiation.” This sentinel piece of physics laid the groundwork for the theory of stimulated emission of radiation, which was later used by the by American physicist Gordon Gould to coin the acronym LASER.

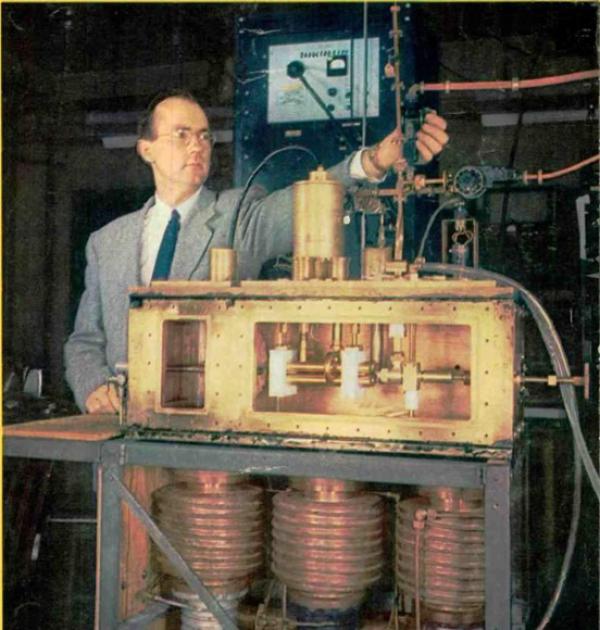

Charles Townes with the first MASER Alamy Stock Photo

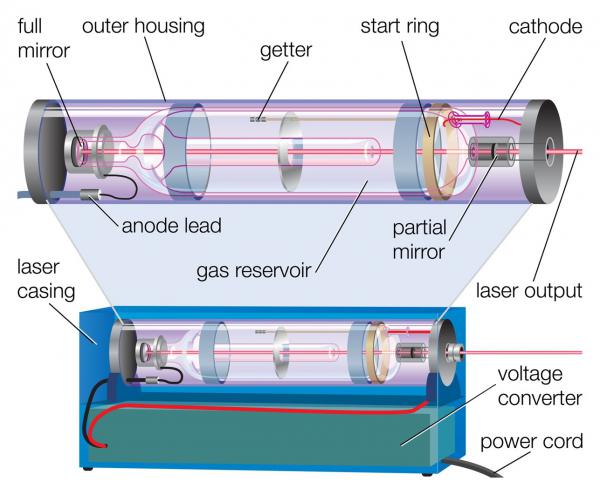

In essence, the word is an abbreviation of the phrase light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation. In 1960, Theodore Maiman working with the Hughes Electric Corporation in California, created the world’s first working Ruby laser. The acronym LASER, although appearing theoretical, is of more than passing interest because it means a laser device must be able to make a new form of light. This light must be composed of one wavelength (colour), it must pass in one direction (coherent), and its waves must be parallel.

These unique characteristics can be used by doctors to achieve different results. We know that different wavelengths can penetrate various depths of the skin, and they can also cause dissimilar effects by targeting differing-coloured lesions.

This means that laser A could be used to target haemoglobin (red) in the broken blood vessels (telangiectasia) of rosacea, while laser B may be used to target melanin (brown) in the hair on an upper lip of a female with hirsutism. It also means that lasers could be used to vaporise water in tissues, thereby causing resurfacing and later collagen stimulation with significant improvements to wrinkles in the skin. In 1961, research was focused on this new technology and continued with the production of a new laser made from crystals of yttrium-aluminium-garnet treated with 1-3% neodymium.

Basic components of a laser Alamy Stock Photo

The world’s first Nd: YAG laser was developed. This laser emitted energy in the near-infrared (IR) spectrum at a wavelength of 1060nm. Although many Americans felt safer to have more powerful lasers being developed, doctors tried to harness its power as they found its high-penetration emission to be useful for vapourising tissues and thermally coagulating large blood vessels.

The laser is still widely used in cosmetic medicine today. It has even found a new role in targeting hair follicles in darker-coloured skin. The following year, the first experiments into depilation by laser took place when Dr Leon Goldman used the principle of selective target destruction with ruby lasers to destroy the melanin in hair follicles. Unfortunately for him, although the idea was good, he did not consider that the laser emitted a continuous wave more adept at targeting melanin in the skin and burnt his patients. The other patients in the experiment suffered from post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation, and the experiment was abandoned.

In that year, the argon laser was also developed. This laser emitted energy in the blue-green portion of the visible spectrum, making it more readily absorbed by melanin and haemoglobin than by the surrounding tissue. In 1963, the ruby laser became the first medical laser when Francis L’Esperance from the Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Centre used it to coagulate retinal lesions.

In 1965, Townes began working with Bell researchers Eugene Gordon and Edward Labuda to design a better laser for eye surgery as the blue-green light of the argon laser is more readily absorbed by blood vessels than the red light of the ruby laser.

After further refinements and experiments, they developed a laser that is still used to this day to treat patients with diabetic retinopathy. It also has a use in the treatment of port-wine stains.

In 1964, Patel at Bell Laboratories developed the CO2 laser. This laser operated at 10,600 nm, and it was like the Nd YAG in that it could be used for cutting materials like stainless steel.

The advantage was that it could also be focused onto a smaller spot, a function that one day could be useful in space. Thankfully for cosmetic medicine at this wavelength, energy is also heavily absorbed by water, which everyone knows is the primary constituent and chromophore of cells in living tissue. This function made the energy generated by the new CO2 laser suitable for tissue vapourisation, and a whole new era of wrinkle removal by skin resurfacing began. The experiments on trying to find the ‘Holy Grail’ of being able to remove hair by laser light followed throughout most of the rest of the sixties. In 1967, attempts were made to reduce skin damage by directing the light energy to individual follicles using a wire-thin fibre optic apparatus. Many of these devices were sold illegally in the United States throughout the late sixties until the FDA banned their use.

In 1968, Union Carbide commissioned a study by Dermascan (manufacturer of the Proteus thermolysis machine) of the effects of applying laser energy applied directly to each hair follicle. The results were largely unsuccessful in that the perceived depilation may have been related to a type of electrolysis effect. Today Union Carbide is more famous, when in 1984, their chemical plant in Bhopal, India, leaked 27 tons of the deadly gas methyl isocyanate into the atmosphere, exposing half a million people to the gas, resulting in the eventual deaths of 20,000 people.

Charles Townes died at the age of 99 in Oakland, California, on January 27, 2015. He was one of the most important experimental physicists of the last century.

You can buy The Living History of Medicine on Amazon for £25.59 for the hardcover, £20.25 for the paperback or £3.50 for the Kindle.